The clavicle, commonly referred to as the collarbone, is situated horizontally at the juncture of the thorax and neck. It serves as a structural bridge connecting the scapula to the sternum, thus contributing to the stability and mobility of the shoulder girdle. The clavicle's palpability under the skin and its superficial location make it vulnerable to fractures.

The clavicle exhibits an S-shaped configuration, with two curves creating medial convexity and lateral concavity when viewed from the superior aspect. This shape allows for resilience in absorbing forces transferred across the shoulder girdle and contributes to the range of motion of the upper limb.

The body of the clavicle has a superior surface, typically smooth in the middle third, and an inferior surface with a nutrient foramen and orientation groove. The clavicle terminates in two extremities: the medial end, or sternal extremity, with a joint surface articulating with the manubrium of the sternum; and the lateral end, or acromial extremity, which articulates with the scapula's acromion, forming part of the acromioclavicular joint.

The scapula, or shoulder blade, is a flat, triangular-shaped bone that lies on the posterior aspect of the rib cage, spanning from the first to the seventh rib. Its primary function is to provide attachment points for several muscles and aid in the wide range of upper limb movements. The scapula's mobility and stability are crucial for the mechanics of the shoulder girdle.

The scapula presents with two faces, anterior (costal) and posterior, three borders (superior, medial, and lateral), and three angles (superior, inferior, and lateral). The posterior face is divided by the scapular spine into the supraspinous and infraspinous fossae. The lateral angle is notable for the glenoid cavity, which articulates with the humeral head to form the shoulder joint.

The coracoid process is a beak-like projection from the scapula which provides attachment for tendons and ligaments such as the coracoclavicular ligament, as well as muscles including the short head of the biceps brachii and the coracobrachialis. This structure plays a pivotal role in stabilizing the shoulder joint and serves as an important landmark for brachial plexus nerve blocks.

The pectoral girdle refers to the shoulder region's skeletal framework and plays a fundamental role in connecting the upper limb to the axial skeleton. This bony girdle is chiefly comprised of two elements: the clavicles (collarbones) and the scapulae (shoulder blades). These components serve as the main anchors for the various muscles that contribute to the complex range of motion associated with the upper limbs.

The clavicle is an S-shaped bone with a superior surface that is palpable under the skin and an inferior surface that articulates with the first rib, giving it vital structural support. The bone has a medial sternal end, which connects to the manubrium of the sternum, and a lateral acromial end, which forms the acromioclavicular joint. The scapula, with its three borders and two surfaces, creates a variety of attachment points for muscles and ligaments. The lateral angle of the scapula articulates with the humerus at the glenoid cavity, forming part of the shoulder joint.

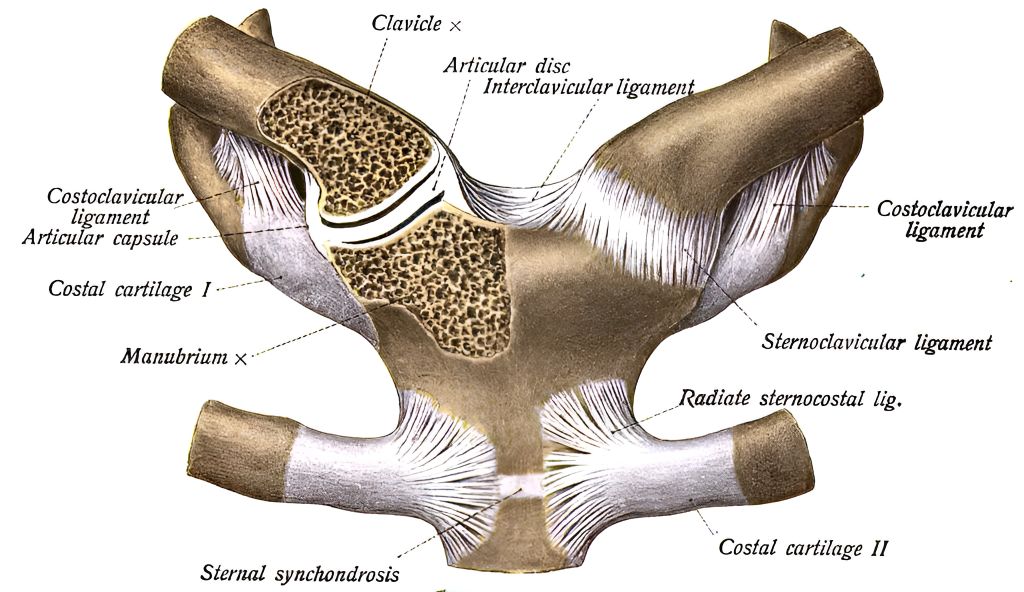

The sternoclavicular joint, a saddle-type joint, links the medially located sternal extremity of the clavicle to the manubrium of the sternum and first rib cartilage. Stability is bolstered by fibrous capsular ligaments and an intra-articular disc, which compartmentalizes the synovial cavity. This joint permits clavicular elevation, retraction, protraction, and axial rotation, essential for shoulder range of motion. The acromioclavicular joint, a plane-type synovial joint, connects the acromial end of the clavicle to the acromion of the scapula, allowing for some "gliding" movement at this junction. Stability here is reinforced by the coracoclavicular ligament, which is instrumental in suspending the scapula from the clavicle.

The sternoclavicular joint, a saddle type, connects the sternal end of the clavicle with the manubrium of the sternum and the first rib's cartilage. This articulation allows for pivotal movement of the clavicle, essential for shoulder mobility, serving as the only direct skeletal attachment of the upper limb to the trunk.

An articular disc bisects the joint into medial and lateral compartments, which enhances congruity and stability while allowing for smooth gliding movements. The medial part interacts with the sternum, whereas the lateral part interfaces with the clavicle, each facilitating different ranges of motion.

The joint's stability is bolstered by the anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments, the interclavicular ligament, and the costoclavicular ligament. While the joint is resilient, trauma can risk injury to nearby structures such as the phrenic or vagus nerves and may compress large vessels.

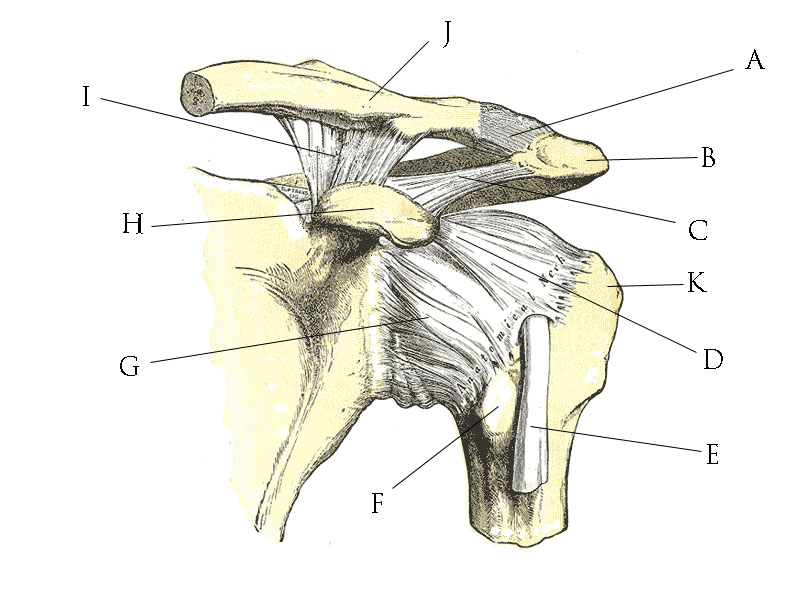

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is a planar synovial joint formed by the lateral end of the clavicle and the acromion of the scapula. Its primary function is to allow for a broad range of upper limb movements including elevation, depression, protraction, and retraction. The articular surfaces are covered with fibrocartilage, and the joint is enveloped in a capsule lined by synovial membrane. Stability is provided by the AC ligament, which is intrinsically weak but is reinforced by the strong coracoclavicular ligaments: the trapezoid and conoid ligaments, collectively forming the coracoclavicular symphysis, playing a crucial role in suspending the scapula and arm from the clavicle.

The AC joint is stabilized by both the acromioclavicular ligament, which covers the superior aspect of the joint, and the coracoclavicular ligaments (trapezoid anteriorly and conoid posteriorly), attaching the clavicle to the coracoid process of the scapula. These ligaments prevent excessive motion and are pivotal in maintaining the integrity of the joint, especially during shoulder movements. The joint is innervated by branches of the suprascapular and axillary nerves. Injury to these nerves can happen with clavicular fractures or dislocations and may result in pain and dysfunction of the shoulder girdle.

The scapulohumeral joint, or shoulder joint, facilitates a wide range of movements due to its ball-and-socket structure. Abduction involves lifting the arm away from the body through an anteroposterior axis, while adduction brings it back toward the midline. Flexion and extension, movements of projecting the arm forward and backward, occur around a transverse axis. Rotational movements include internal and external rotations around a vertical axis. Circumduction is a composite movement combining flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction in succession.

The musculature surrounding the scapulohumeral joint forms a musculo-tendinous cone with deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres major, teres minor, and subscapularis. The deltoid muscle is prominent in abduction, especially after the initial 15 degrees taken over from the supraspinatus. The supraspinatus initiates abduction, while the infraspinatus and teres minor are responsible for external rotation, and the subscapularis facilitates internal rotation. The teres major and latissimus dorsi contribute to adduction and internal rotation.

Innervation of the shoulder muscles is vital for coordinating these complex movements. The axillary nerve supplies the deltoid and teres minor, allowing for abduction and external rotation. The suprascapular nerve innervates the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, initiating abduction, and providing external rotation, respectively. The subscapular nerves, both upper and lower, innervate the subscapularis, which is responsible for internal rotation of the shoulder joint.

The deltoid muscle, named for its triangular shape, is a prominent feature of the shoulder. It is subdivided into clavicular, acromial, and spinal parts which converge on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. Anteriorly, fibers originate from the lateral third of the clavicle, medially from the acromion, and posteriorly from the scapular spine's lower edge. Each part plays a distinct role in shoulder movements.

The deltoid is pivotal for arm abduction, flexion, extension, and rotation. Its anterior fibers flex and internally rotate the arm, while posterior fibers extend and externally rotate it. The middle fibers are chiefly responsible for abduction. Deep to the deltoid, the muscle overlays the rotator cuff muscles, which are integral in stabilizing the shoulder joint during the deltoid's powerful actions.<\p>

Innervated by the axillary nerve, the deltoid's function is vital for shoulder mobility. Injury to this nerve can result in deltoid paralysis, characterized by a drooping shoulder and compromised arm abduction—a clinical syndrome known as "deltoid paralysis." Conversely, deltoid muscle hypertrophy or inflammation can compress this nerve, affecting its normal function. Additionally, the deltoid region is common for intramuscular injections, where its thick muscle mass safely accommodates medications.

The supraspinatus muscle originates in the supraspinous fossa of the scapula, covered by the trapezius. It converges to a tendon inserting on the greater tubercle of the humerus. This muscle is crucial for the initial 15 degrees of arm abduction, working alongside the deltoid, and acts as an active stabilizer of the glenohumeral joint by holding the humeral head within the glenoid cavity. Innervation is through the suprascapular nerve.

The infraspinatus muscle fills the infraspinous fossa and extends to a tendon that attaches to the middle facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus. Functionally, it externally rotates the humerus and supports the shoulder joint by keeping the humeral head pressed against the glenoid cavity. It also has a protective role in stabilizing the joint capsule. Innervation of the infraspinatus is likewise via the suprascapular nerve.

Situated adjacent to the infraspinatus, the teres minor originates from the dorsal aspect of the axillary border of the scapula and extends to the inferior facet of the greater tubercle. Functionally, this muscle aids in the external rotation of the humerus and reinforces the capsule of the shoulder joint, contributing to joint stability. The teres minor muscle is innervated by the axillary nerve, distinguishing it from the infraspinatus.

The rotator cuff comprises four muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. These muscles stabilize the glenohumeral joint by keeping the humeral head within the shallow glenoid cavity. They actively modulate rotational and abduction movements, ensuring the joint's functional integrity during varied arm maneuvers.

Abduction primarily involves the deltoid and supraspinatus muscles, while the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi execute adduction. The rotator cuff plays a crucial role: the infraspinatus and teres minor externally rotate the humerus, and the subscapularis is a strong internal rotator. Combined actions of these muscles allow for complex shoulder motions, such as circumduction.

Shoulder muscle integrity is vital for upper limb function. Rotator cuff injuries can severely impair mobility, leading to conditions like impingement syndrome or rotator cuff tendinitis. Overhead activities can precipitate such injuries, necessitating thorough clinical examination and interventions such as physiotherapy or, in severe cases, surgical repair to restore normal shoulder function.

The clavicle is a horizontally situated S-shaped bone that connects the scapula to the sternum, providing stability and motion to the shoulder girdle. The body of the clavicle has two distinct extremities: the sternal end, which connects to the sternum, and the acromial end, which forms the acromioclavicular joint. The scapula is a triangular bone in the upper back, key to shoulder mobility and muscle attachment. It has two faces, three borders, and three angles, with the lateral angle featuring the glenoid cavity for the shoulder joint. The coracoid process serves as a critical attachment point for muscles and ligaments.

The pectoral girdle, comprised of the clavicles and scapulae, connects the upper limbs to the axial skeleton and enables a complex range of motion. The sternoclavicular joint, a saddle-type articulation, and the acromioclavicular joint, a plane-type synovial joint, allow for diverse movements and stability of the area. These joints are supported by various ligaments and innervated by surrounding nerves. Movements of the scapulohumeral joint include abduction, adduction, flexion, and rotation, made possible by muscles, such as the rotator cuff group and the deltoid, which are essential for shoulder motion and stability.

The deltoid muscle is a key shoulder muscle, involved in abduction, flexion, and rotation, receiving innervation from the axillary nerve. The rotator cuff muscles, including the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor, stabilize the shoulder and facilitate various movements like abduction and external rotation. These muscles are susceptible to injury from activities that tax the shoulder, potentially leading to mobility issues and necessitating clinical interventions.

Anatomy, Clavicle, Thorax, Neck, Collarbone, Scapula, Stability, Mobility, Shoulder girdle, Fractures, Anatomy, Scapula, Thorax, Rib cage, Muscles, Upper limb movements, Anatomy, Scapula, Faces, Edges, Angles, Scapular spine, Coracoid process, Landmark, Brachial plexus, Ligaments, Pectoral girdle, Clavicles, Scapulae, Upper limbs, Anatomy, Clavicle, Parts, Sternal extremity, Acromial extremity, Glenoid cavity, Sternoclavicular joint, Acromioclavicular joint, Sternoclavicular joint, Structure, Function, Articular disc, Ligaments, Nerves, Acromioclavicular joint, Coracoclavicular symphysis, Planar synovial joint, Ligaments, Nerve, Scapulohumeral joint, Abduction, Adduction, Flexion, Extension, Muscles, Shoulder movements, Innervation, Deltoid muscle, Insertions, Actions, Relationships, Innervation, Clinical implications, Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres minor muscles, Anatomy, Function, Arm abduction, External rotation, Innervation, Rotator cuff, Muscles, Shoulder movements, Abduction, Adduction, Clinical implications, Shoulder muscle function, InjuriesComprehensive Overview of the Musculoskeletal Structures of the ShoulderThe Shoulder0000